For those that don’t know, May is Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. It’s a month for our nation to reflect on how Asians and Pacific Islander, including Native Hawaiians played an important part in the history of the United States.

I could probably go on about how Chinese Immigrants pretty much built the Transcontinental Railroad. Or how Filipino American farmers in California were the first to walk off the grape fields, prompting the beginning of the Delano Grape Strike led by Cezar Chavez.1

I can even remind everyone that Filipinos were the first Asians ever to set foot in the Americas. Most are told that the first colony in the United States was founded at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 by English settlers. However 20 years prior to this, on October 18, 1587, Filipino sailors working on a Spanish ship arrived to what is now known as Morro Bay, California.

IF LIFE GIVES YOU MELONS, YOU MIGHT BE DYSLEXIC

The story I choose to tell today is one that many of my Filipino American may be aware of, but do not know much about it. After all, I had only known tidbits of it until our recent trip to New Orleans, Louisiana.

When I was in high school, I was at a party for one of my many distantly related Tita’s from my Dad’s side of my family. At that party was a cousin twice removed of my 5th aunt’s husband’s sister’s daughter’s son – oh who am I kidding … we’re all related somehow, aren’t we? Seriously though, I was speaking with a cousin of one of my cousin’s who lived in Mississippi. For some reason, we ended up talking about where many of the Filipino Communities are in North America. In the Metro Detroit area today, I’d say Bloomfield Hills, Sterling Heights, and Canton. This cousin mentioned cities in his area, but also mentioned that New Orleans had the largest Filipino Communities because that’s where the first Filipinos settled in North America.

To hear this information was a surprise for me. I always thought that it would be California or even New York, as that’s where most of my Gen-X friends’ parents or grandparents came into the US. Since then, I wanted to learn more about this. However, at that time, research involved things called encyclopedias or microfiches. It involved finding books utilizing the Dewey Decimal System after finding books by subject or author in things called card catalogues.2

THE EARLY BIRD CATCHES THE WORM …

BUT THE SECOND MOUSE GETS THE CHEESE

When our travels as Eclipse Chasers took us south to Arkansas this past April, Hubby and I decided to knock off a few more States on our quest to visit all 50 States and Louisiana was one of them. Both of us had been to New Orleans separately for work, but never together and not long enough to enjoy the city. I planned for us to stay three nights there, just so we can enjoy Crescent City at our leisure. While planning, I wanted to see if I could visit the area where the first Filipinos settled. Now that Google existed, I was able to find much more information about my heritage. And the first thing I found was astounding.

Not only was New Orleans – or rather southern Louisiana – the first settlement of Filipinos in the Americas, but these Filipinos were one of the very first Asian American settlements in the Americas. Imagine that!

WHEN THE CAT’S AWAY, THE MICE WILL PLAY

So, here’s the story. Close to two centuries after that first landing in Morro Bay, Filipino sailors – again enslaved by Spain grew tired of their abuse and deserted the ships. They hid in the marshlands of Louisiana and eventually settled into a bayou about 30 miles southeast of New Orleans. The area was isolated, prone to storms and mosquito infested (much like many rural areas in the Philippines), but it was a perfect place to hide from the Spainards. They eventually became known as the Manilamen.

Along with other enslaved people and other people of color, the Manilamen built a small fishing village they called Saint Malo. They built small houses of wood and palmetto fronds on stilts, much like nipa huts or bahay kubo homes in the Philippines. They became skilled fishermen, as the lands – deeper into the wetlands than most were willing to travel or work, proved fertile for fish in the spring, shrimp in the summer, and oysters in the fall.

As fisherman, the Manilamen contributed to the local seafood industry (and eventually the entire region) to make Louisiana one of the largest exporters of shrimp nationwide. First, they used our methods of drying shrimp and smoking fish (tinapa!) to preserve food before the invention of refrigeration. Then the Manilamen revolutionized the shrimp drying industry by utilizing a method used in the Philippines to speed up the process of separating shrimp shells from its meat. This method, known as “Dancing the Shrimp,” did this by dancing and stomping on piles of shrimp in a circular motion. This made Saint Malo a wholesale market for local sea merchants. In later years, Filipinos in Louisiana thrived were well-known in the industry and eventually several shrimping facilities came to use the same method.

YOU CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER,

BUT YOU CAN JUDGE A PERSON BY THEIR SHOES

Because of its remote location and prime fishing spot, Saint Malo was often a port of departure for tourists wanting to go fishing further south into the shores towards the Gulf of Mexico. Though many local New Orleanians knew of the Manilamen, there was not much documented about them.

However, stories in New Orleans about them – most of them folk lore — existed. It’s been mentioned in letters and journals that the Manilamen of Saint Malo were uncivilized and that the living conditions were uninhabitable. That there was no governance in their society – police, courts, laws, for example. The Manilamen were said to be savages as the village was made up of only tribal men. They had been described as prehistoric savages that despised women and would do great harm to any female they encountered. While it was true that the village was originally all Filipino men – as slaves from the Spanish ships that they fled from, the Manilamen did have wives and children. As they became more integrated with their local society, they would marry and raise families in New Orleans while staying at Saint Malo to work during the week.

Because of racist immigration laws such as the Nationality Act of 1790, Asian women were not allowed entry into the United States. In addition, there were racist laws that prohibited marriage between white and non-white people. And so the Manilamen instead married women from other communities of color. Many married into nearby Isleño, Cajun, and indigenous communities.

THE COCONUT DOES NOT FALL FAR FROM THE TREE

In the late 1800’s on the southern end of Louisiana, another group of Filipino fishermen and sailors lead by local fisherman Quintin de la Cruz, established Manila Village. It was one of several Filipino shrimp drying facilities in the area which also housed the workers and their families in nipa huts or bahay kubo homes around the edges of the shrimp drying platforms. Not far from Manila Village, a smaller version of Manila Village was built by a group of Filipinos led by John (Juan Roxas) Rojas called Clark Cheniere.

By the 1930’s the shrimp drying industry had reached their peak and improved methods of canning and refrigeration meant less manual labor was needed. In addition, storms were always a constant threat to the area which drove many families to higher grounds. Saint Malo was destroyed during the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915. A storm in 1947 destroyed most of Manila Village and in 1965, Hurricane Betsy flattened the entire village. Though not confirmed, I believe Clark Cheniere may have been destroyed during the same hurricane.

BETTER LATE THAN NEVER, BUT NEVER LATE IS BETTER

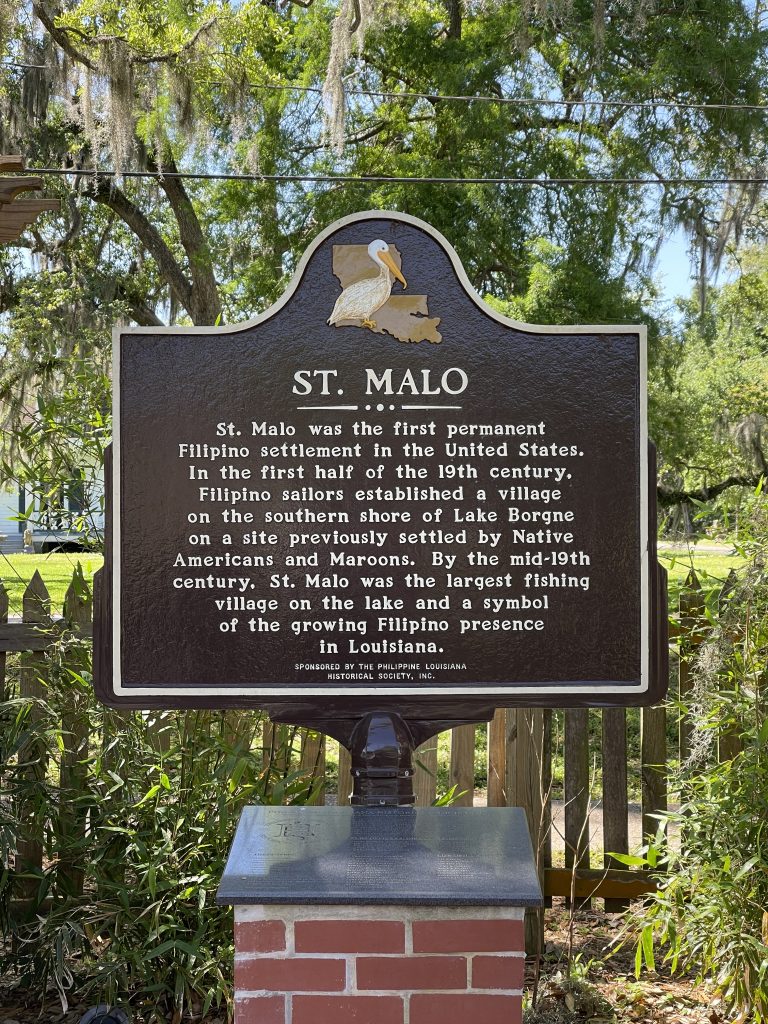

So this is how on a hot April day, Hubby and I ended up at the Los Isleños Museum Complex in St Bernard LA, standing next to the historic marker for Saint Malo. After a lot of research on the interwebs, I stumbled upon the Filipino LA website which helps make the stories of Filipino Louisiana available to the public. This then led to finding about about Saint Malo, the Manilamen, and Manila Village. Further research led me to Louisiana State Markers and their locations. While Saint Malo no longer exists, a marker was set up in St Bernard Parish closest to where Saint Malo would have been.3

There are two other markers for Manila Village and Clark Cheniere located on Manila Plaza in front of Jean Lafitte Town Hall in Jefferson Parish. I wish we had more time, but we couldn’t drive to both locations within the time frame that we were in New Orleans.

WHEN LIFE GIVES YOU LEMONS, MAKE CALAMANSI JUICE

While in New Orleans proper, we did make a visit to the NPS French Quarter Visitor Center. The displays went through the history of New Orleans and how it became an important port of call in the trade industry. They talked about the lands and the population and its indigenous population. It also spoke of its Creole, Spanish, and French history … but no mention of any Filipino history.

Strange, I thought. Especially since the research I did indicated that Filipinos played a huge part of the New Orleans and Louisiana history. Of course I had to ask one of the park rangers about this. To my surprise, they were well aware of the history of the Maniliamen and Manila Village. Both park rangers talked about how they used to have a huge display about the Filipino contributions to the region. They even talked about the “Dancing the Shrimp” method and the houses on stilts. Apparently a few years back, they revamped the displays in that visitor center and most of the Filipino displays were removed.

Reflecting on it now, the markers for Manila Village and Clark Cheniere were close to the NPS Bataria Preserve within the Jean Lafitte National Historic Park & Preserve. This would have probably taken us closer to where the villages were at. And perhaps this visitor center would’ve had more information about Filipinos in Louisiana. Maybe on another trip we will get down there to visit it. D’oh!

IF THE SHOE FITS, WEAR IT

If you are Filipino and are ever in The Big Easy, Crescent City, NOLA, Nawlins, Birthplace of Jazz, or any other name you’d like to call New Orleans, I highly recommend checking these places out. There isn’t much to see, but knowing that your ancestors had been one of the first Asian Americans to settle in the Americas at that location is pretty damn cool.

PS. Hope you enjoyed the titles of each section 😂 Most of my Filipino American friends would know that these are phrases many of our parents have used on us in the past

- Only after being prompted by the Filipino Union Leader that led the first strike, Larry Itliong ↩︎

- Basically it was way before the advent of the internet and AOL or AltaVista or AskJeeves. If you don’t know any of those search engines then you are definitely Gen-Y ↩︎

- Of note, Islenos are descendents of colonists of Spanish Louisiana between 1778 and 1783 who were primarly from the Canary Islands and intermarried with other communities such as Filipinos, French, Creoles, and Hispanic Americans. This is why the Saint Malo marker is at the Los Islenos Museum Complex. ↩︎

Great to see you posting, Emily! 🙂 And thanks for the history lesson — so interesting!