Roadtrips, Internment, and Vandalism, Oh My!

Part Two in my ongoing series about Asian Americans

(Part One begins here)

It’s funny about history. When we look back, we can recognize that many historical events occurred during times of uncertainty and fear. Most wars have been based on anger, hatred, and (let’s face it) ideas or goals are different and that one feels that their own is important. It’s based on fear of the unknown; the uncertainty of what may happen next. Take, for example, the Japanese Internment camps.

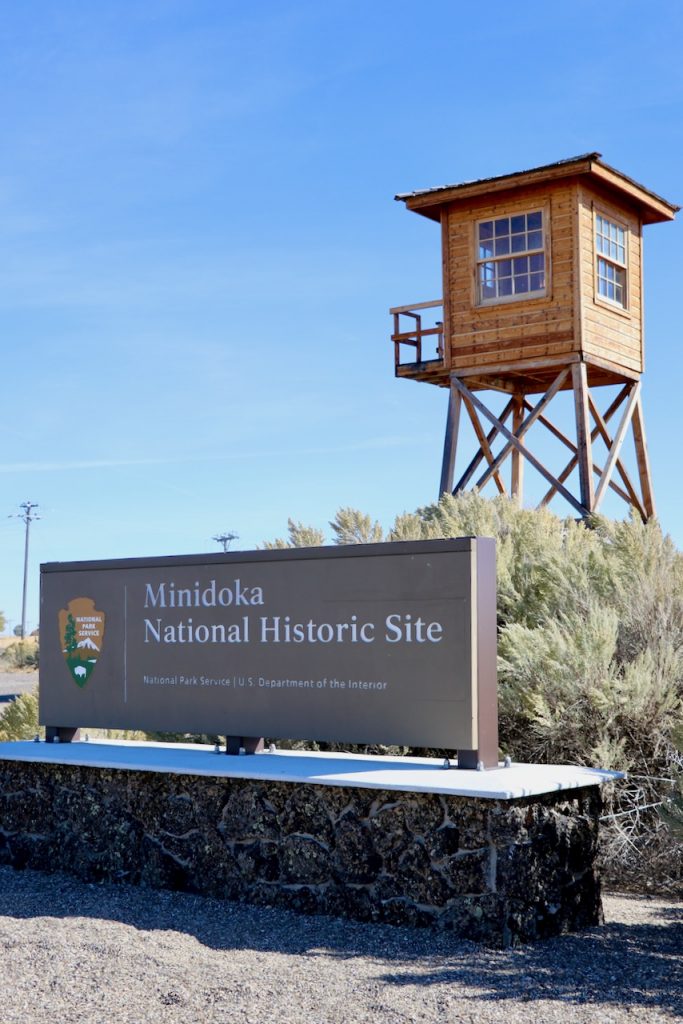

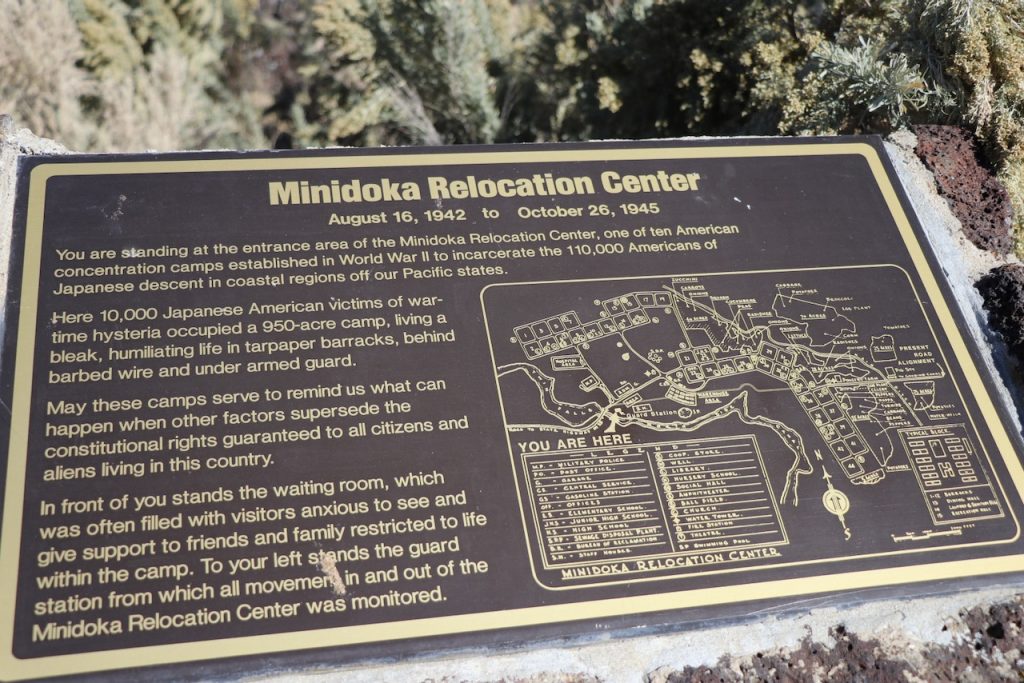

On our 2017 West Coast Road Trip, Hubby & I planned a stop at the Minidoka National Site in Jerome, ID on the drive home. We both wanted to understand why this country would take Japanese Americans away their homes and businesses for the “safety of America.” Why this country would force them into remote areas that were not suitable for doing anything else but farm. Why did they fear that all Japanese were spies for Japan?

While walking around the site, we saw one of the tar paper-covered barracks where these Japanese Americans lived. Each barrack was divided into small rooms where an entire family (sometimes as large as 8) were expected to sleep and eat.

As Minidoka was hastily constructed and incomplete, many of these barracks would fall apart. The type of wood used to construct the barracks shrank over time, bringing about structural imbalance which could cause them to shift or sink. The tar paper easily ripped apart, leaving some with no privacy.

We saw what the internees’ daily life would entail. Providing unpaid labor to complete the camp under the military commander’s order is one example. They also learned to farm in order to provide sustenance for themselves is another example. For entertainment (and only in the warmer months), they would play baseball on a field that they made. Imagine having to build your own prison and then farm for your meals. While I can never experience what they went through, I was so angry that a “civilized” nation would do this to their own citizens.

After the war, these Japanese Americans were “released.” Yet since they had been forced to vacate their homes and abandon their lives (within two weeks or less) prior to being incarcerated, they had no longer had a “home.” Despite being given a small stipend to “restart” their lives, most found their homes occupied, their businesses taken over. For that reason, many of these internees wished to stay on the land.

These Japanese Americans knew that their jobs were taken and they would face discrimination when trying to find a new job or start a business. Many of them knew nothing outside the camp as they were interned at a young age. They never knew what life was like outside the camp. Most of these younger Japanese Americans only knew how to farm potatoes (they were in Idaho, after all), so they saw purchasing the land that they lived on as an opportunity to “reset” their lives. Yet, despite the request to purchase the land, they were never even given the opportunity to bid for it. Instead, the US Federal Government allotted the land for white WWII vets.

Much of Minidoka is now bereft. All but two tar paper-covered barracks remain, but the guard towers, and most of the barbed-wire fences are now gone. Today, this land is considered a part of the National Parks Service and is registered as a National Historic Site.

Every time I reflect back on that visit, I also remember that day in grade school where we learned about the European concentration camps. I remember being told that over 6 million persons of Jewish descent were forced to uproot their lives and placed in those camps. And how close to 2 million had died in one simply because of who they were and could not change. I remember how horrified my entire class was to learn that this happened before and during WWII. And how it’s been considered a taboo topic, yet everyone throughout the world acknowledges that that it happened. [i]

(And before I say what I’m going to say, let me be very explicit that I – by no means – am comparing these events with one another. Nor am I trying to undermine what happened in Europe. My hope is that you continue reading with an open mind.)

I find it interesting that more Americans remember what happened in Europe. And I realize that talking about Japanese Internment Camps are also a taboo subject. I just find it – what’s the word – disheartening that, to this day, many Americans don’t know about these camps [ii] nor do they acknowledge (or want to acknowledge) that America also disrupted the lives of its own residents because of something they cannot change.

Take a moment to reflect on that. And then, even though it’s taboo, talk about it. Educate others. Read more about it. This, to me would be one way of acknowledging that Minidoka and the 10 other Japanese Internment camps existed. And point out that we, as US citizens essentially did the same to Japanese Americans that Germany did (albeit, much more extensively) in Europe.

Our next trip out west will be a stop in Seattle. [iii] We want to see the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial; a city where most of the Japanese Americans from Washington, Oregon, and Northern California, were sent to prior to being shuttled by bus (with the shades pulled down) or train to Minidoka. We want to learn more about this period of American History that hasn’t been readily taught in schools.

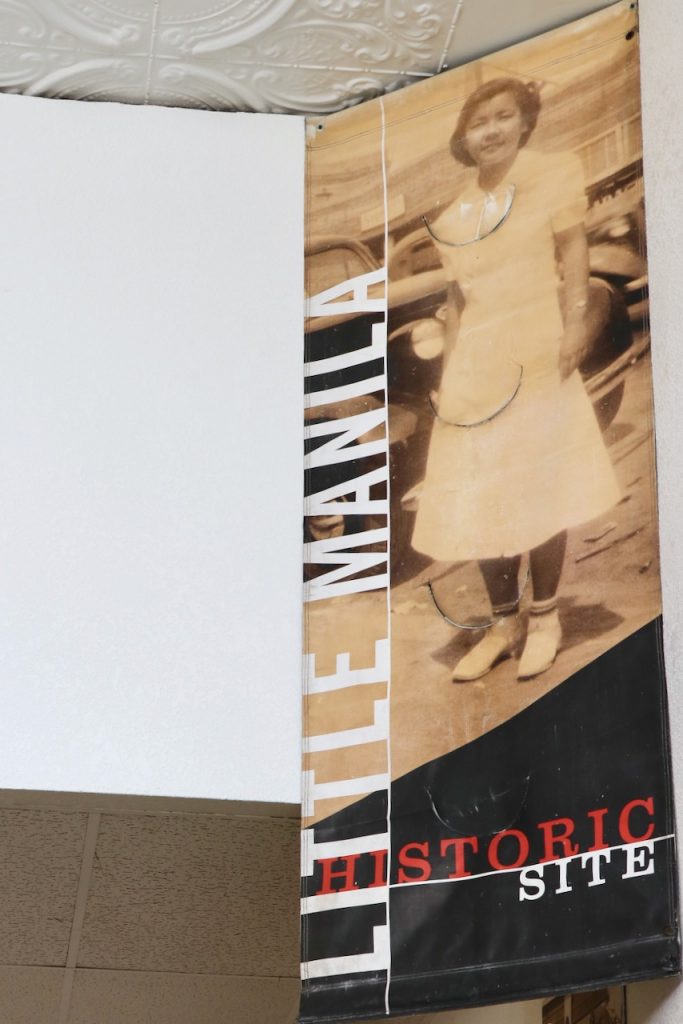

On that same trip, Hubby & I made a side trip to visit the Little Manila Center in Stockton, CA. On the drive out west, we heard news about vandalism to the front entrance of the Center. Words like “whittie” and “bigotted” were scrawled onto the windows (later to be to be interpreted as “white property, you’re a brainwashed bigot”).

Included in the vandalism were display banners, which were put up to celebrate Filipino American History Month. What was more damaging was the loss of donated photographs from a time in history where Stockton was the largest Filipino community in the United States. Though many viewed this as a hate crime, ultimately local authority ruled it simply as an “act of vandalism,” which is a felony charge if damages exceeded $400. [iv] No one was ever caught.

When we arrived, we were greeted by the Co-founder and Executive Director of Little Manila Rising, Dillon Delvo. Despite being in the midst of a group Zoom meeting, Dillon was gracious enough to provide us with a one-on-one tour of the Center and stories behind many of the artifacts displayed. He painted a vivid picture about the lives of Filipinos in 1920-1960’s Stockton that I will never forget.

For instance, did you know that Filipinos were the first to set foot in what would eventually be Morro Bay, CA 33 years before Pilgrims from England arrived at Plymouth Rock? Mind you, they came over as low-paying servants of a Spanish fleet trying to establish a trade route from Cebu, Philippines to Acapulco, Mexico. This landing happened on October 18, 1587 which is why October is known as Filipino American History Month throughout the US.

More importantly was the story of how downtown Stockton came to be known as Little Manila. In the 1920’s and 30’s, Stockton became a popular destination for young, single, Filipino men who came to be referred as “manongs” [v] who migrated to the area for promises of a job as a farm labor and a good wage. These men came to the US in order to establish a better life for their family back home. Unfortunately, the wages were cheap and the labor was, at times, unbearable under the California sun.

Due to “laws” that only allowed Filipino men to immigrate, [vi] there were no Filipina women in the area. Stockton became a central place for other manongs to reconnect with friends from the same province. Filipino shops lined the streets to help them feel at home. Many of them would come to drink the bars and gamble at gambling dens, spending what little wage they earned. Many of them had a room in the Filipino Federation Building and stayed there until they were able to find (and afford) their own place.

At the Filipino Federation Building they often held social events with dancing and singing. Many of the local white women would attend these dances, as the Filipinos in Stockton were good dancers. Obviously, this made other non-Filipino men angry, claiming that it was against the law and forbade any Stockton women to go to Little Manila or be seen with a Filipino. From there, local places in the city began hanging up signs stating, “No Filipinos Allowed.”

Looking back at this time period, the Anti-Filipino sentiment likely stemmed from the lack of job opportunities during the Dust Bowl era and the Great Depression. Migrant workers feared that the Filipinos, known for their hard work ethics, were stealing their jobs. Aggression from white nativists in this time period was plentiful for all non-white persons, which produced fear that Filipinos were taking over the land that the believed was rightfully theirs. [vii]

The first recorded incident of violence against Filipinos in the US happened on New Year’s Eve 1926, where “Eight whites and Filipinos were stabbed and beaten when white men entered Little Manila’s hotels and pool halls.” They were, according to news reports, “looking for Filipinos to attack.”

On January 29, 1930, a white mob bombed the Filipino Federation Building. Local papers wrote about how “whites in an automobile hurled a bomb into the building, blowing the façade clear across the street and throwing occupants of the club from their beds.”

Incidents as those happened quite readily (one reported that a group of 22 white men spent 5 days looking for Filipinos to shoot) until WWII when Filipino Military and Filipino Americans who signed up for duty suddenly became allies by fighting alongside in battles. Yet, despite being “allies,” Filipinos and other Asian immigrants were deemed “inferior” to the whites. That sentiment still applies today; and the violence to Asians & Asian Americans of late is proof that this remains an issue.

Here’s another little-known fact: Did you know that Filipino Americans in California led the way in unionization efforts amongst ALL immigrant farm workers in the 1930s and 40s? In fact, Larry Itliong, a Filipino union leader was the driving force behind the famous Delano Grape Strike, yet Cesar Chavez is the one that was given credit for starting the strike.

In fact, Filipino farm workers were the first to walk off the grape fields establishing this famous strike. Other ethnic farm workers did not join as they were afraid of retribution from the owners. Itliong then appealed to Chavez & his fellow Mexican laborers and other ethnicities to join the strike. Unfortunately, Chavez became the face of the Delano Grape Strike and Itliong’s important role was overshadowed. [viii]

There’s not much left of the original Little Manila. In the 1950s and 1960s, large sections of Little Manila were bulldozed by the city to “improve” the look of the downtown area. There are no streets named after Itliong; [ix] though there are for Cesar Chavez throughout the country. Other than a street post with a sign to mark a historic site, there is no real evidence of Little Manila in Stockton. The space in which the largest number of Filipino Americans lived was replaced by a freeway, displacing many Filipino homes and establishments.

In fact, before hearing about the vandalism in Stockton on our road trip out west, we were already informed that Little Manila Rising was trying to save the last large lot of what was Little Manila. Unfortunately, they were not successful and a McDonald’s restaurant replaced the once historic site.

Most recently the Rizal Social Club succumbed to demolition. Little Manila Rising were first notified about the city’s plan to bulldoze the building down in mid-July of 2020. The demolition was scheduled for the end of that month, despite ongoing talks within the City Council. Advocates for Little Manila managed to get an extension into the end of August, but the cost of repairing the damage to the building would have left them with no funds to keep the Little Manila Center open. On October 22, 2020 the Rizal Social Club building was torn down.

I’m sharing all these examples because it’s important everyone knows that America has a long history of marginalizing other ethnicities. From the beginnings of colonizing North America, through the Great Depression. From the Delano Grape Strike to removing Filipino American history by destroying important landmarks. This can be said of every Asian ethnicity.

In fact, many Chinatowns, Koreatowns, et al had been destroyed over the years with the guise of “improving the city.” Detroit’s original Chinatown had been demolished in the 60’s to make way for the Fisher Freeway. Currently the majority of the former Chinatown is now the MGM Casino.

Instead, the City moved Detroit’s Chinatown further northeast to the Cass Corridor. This left Chinese American residents without a home and a job. Anyone who has driven through the Cass Corridor in the mid-80’s to the 2000’s knows that it was not a very welcoming neighborhood. Although Wayne State University [x] is just blocks away and Woodward Avenue just one block east, not many Asian Americans of my generation and on had ever been interested in touring the area, simply because we were too young to remember what Detroit’s Chinatown may have looked like.

Today, Cass Corridor has been “revived.” Restaurants and bars have opened up in the area. New condo buildings replaced older homes & businesses in disrepair. There is even a frickin’ Whole Foods Market just a block away from Cass Ave. Yet there is little to show that this used to be Detroit’s 2nd Chinatown; mainly because all the Chinese Americans left.

After visiting Stockton and Minidoka, I do believe that “beautifying” the land / city, is one of the many ways that try to erase parts of white American History that we “don’t like” or even remember. The point of American History is to remember these types of circumstances; even more so, understand the context behind these events. And talk / write / debate about these events. If we fail to remember or even speak about it, then that history will disappear. That is certainly what’s occurring today, as many fail to remember (or refuse to learn about) these events and the circumstances behind them. As the quote says, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.”

Our previous president’s is a prime example of someone that refuses to understand context, or that actions all have circumstances. During the 2020 Presidential campaigns and in response to the New York Times’ (NYT) 1619 Project, he blatantly announced (at the National Archives Museum, of all places) that the current history lessons being taught in our schools are “toxic propaganda.”

On November 2, 2020 (on the day of the 2020 Presidential Election), Trump established by Executive Order the “1776 Commission. He threatened to cut federal funding to schools that teach the 1619 Project and/or use of the Critical Race Theory. He also indicated that funding for the schools that fail to instill “patriotic education” in their curriculum will also be cut.

This 1776 Commission’s goal was to end what Trump called the “radicalized view of American history” in which Trump claimed was an attack on our Founders. In true Trump fashion, he hand-picked the 18-person group, none of which are an American Historian by profession. Then two days prior to the end of Trump’s term, the 1776 Commission released their report.

Hours after the inauguration of our current president, an executive order was issued dissolving the 1776 Commission.

So that’s my history lesson; my way to talk about these tragic events. I write about it because it’s necessary to look at history and all of its actions & consequences to these occasions so we can learn from our mistakes, let alone repeat it over and over.

(More to come in Part 3)

[i] It’s funny (but not) that I happened to stumble on this article while writing

[ii] Mostly because the Gen-Y & Millennials no longer had family that can remember certain event, as the numbers of The Greatest Generation are dwindling. Many don’t even know the names of the Jewish concentration camps, let alone any of the Japanese internment camps

[iii] And, let’s face is … a mini car ride to Lake View Cemetery to pay our respects to Bruce Lee.

[iv] Estimated cost of damage for this act of vandalism was approximately $800. Anything lower than $400 is considered an act of graffiti and is only a misdemeanor; while vandalism is considered a felony.

[v] Manong loosely translates to older brother or uncle

[vi] These local laws were established under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1924

[vii] Which, IMHO, is a joke since – well, besides the Native Americans, Filipinos were the first to step on US soil in Morro Bay.

[viii] Have you heard of Larry Itliong street anywhere? Neither have I; however, I do see a lot of Cesar Chavez streets in some – okay, most major cities.

[ix] He does have a school, a bridge and a day named after him, though!

[x] Interesting fact; Wayne State’s Walter Reuther Library has the original Larry Itliong papers